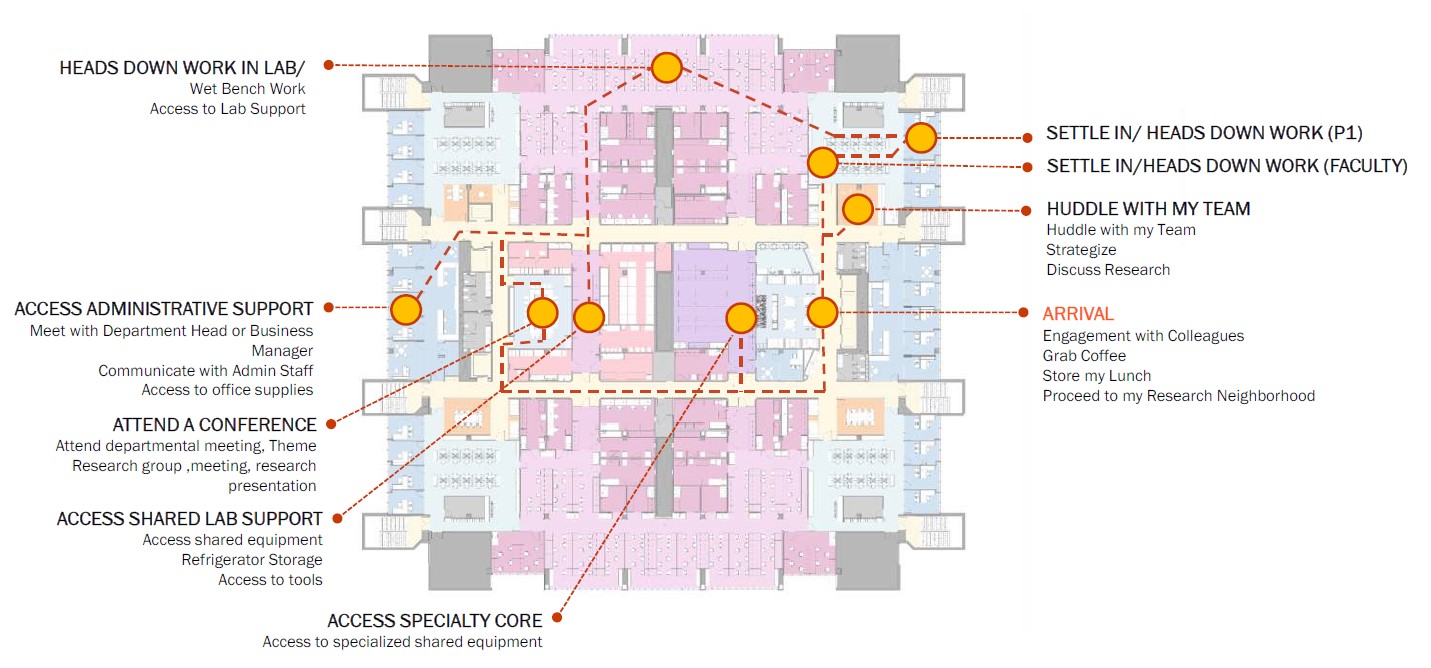

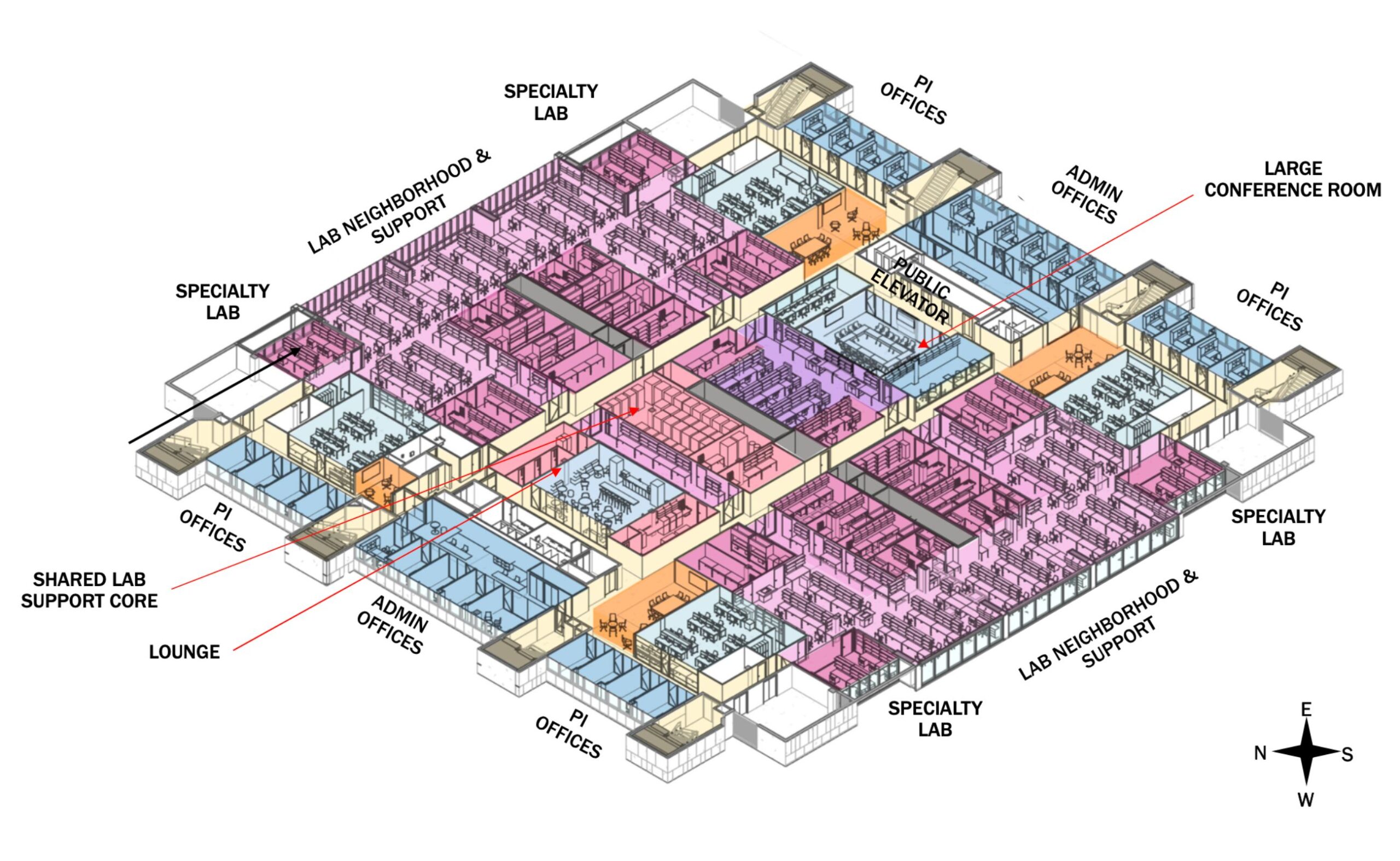

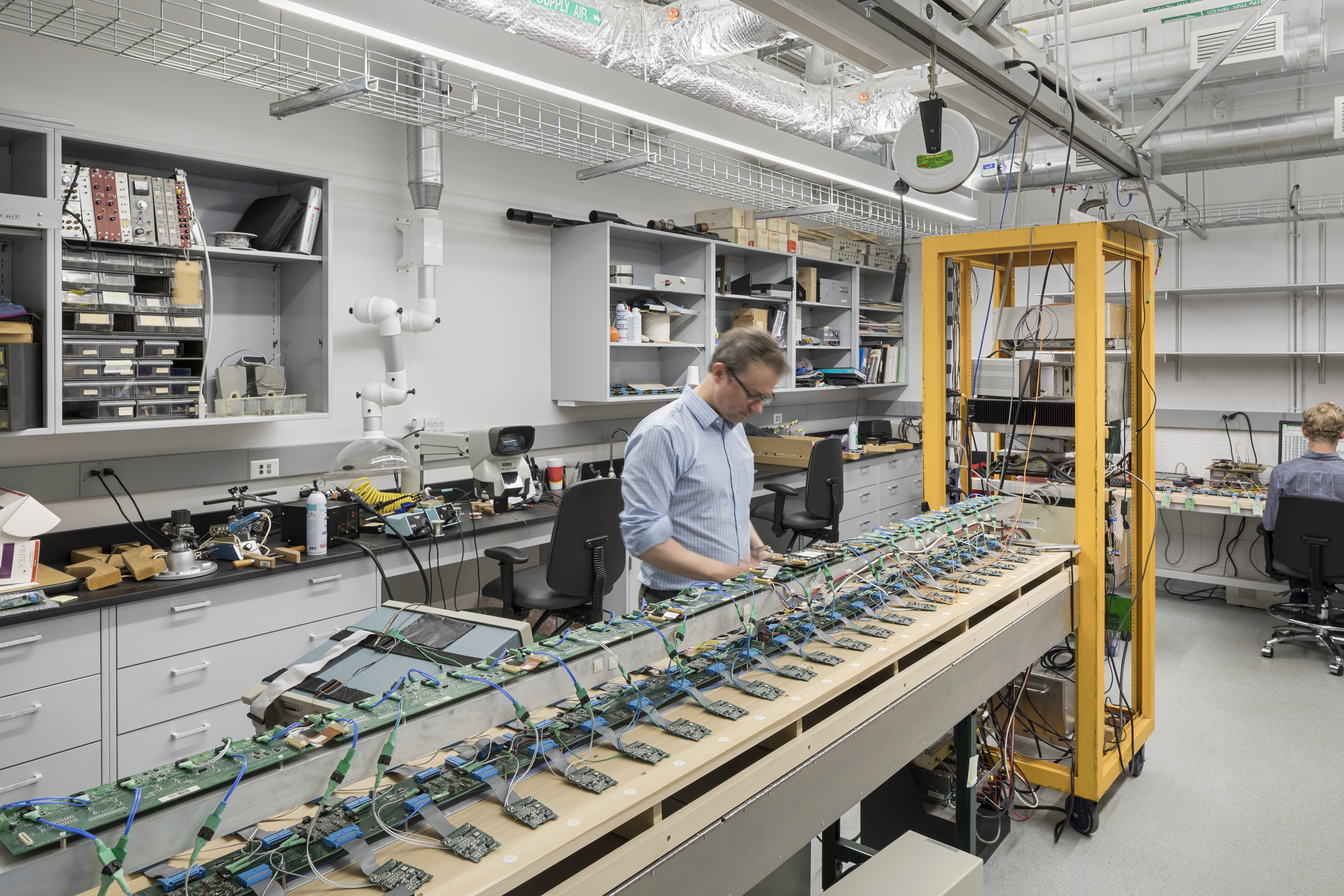

Dr. Steve Nelson joined the faculty at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in 1984, three years after its Medical Education Building (MEB) first opened. A lot has changed on the New Orleans medical campus in the past 40 years: Nelson is chancellor of the Health Sciences Center, now known as LSU Health, and he’s overseeing a complete overhaul of the MEB’s top three floors, which are dedicated to biomedical research. Rather than the cellular, siloed nature of the labs in the original layout, the new, open-plan design aims to realize a metaphor Nelson has used for years with his researchers, comparing them to LSU’s champion football team: sometimes the quarterback is the one who wins the game, and sometimes it’s the receiver; but neither can do it without the full team’s support. “That’s how we should do research,” he says, “so how do you construct a space that fosters teams and facilitates teams?” Perkins Eastman, in partnership with MultiStudio, responded with an adaptable design that transforms how research and discovery will take place now and into the future.

The renovated floors will feature light-filled open labs, shared scientific and computing resources, and communal areas to exchange ideas. When he first joined the faculty, “everyone had their own grant, their own space, their own equipment,” Nelson says. “This is a new day. It’s a whole rebirth of our research enterprise.”