The Meaning of Success

Beyond tolerating jet lag and long absences from home, Perkins says, “To be successful internationally, you really have to enjoy it. You really have to enjoy learning about a new culture, making friends in the culture, and enjoy being there—that’s really important.” Perkins’ enthusiasm is palpable. A prolific storyteller, he delights in sharing memories about important foreign commissions sealed by scoring opera tickets for company executives—or winning drinking contests. “The ability and willingness to eat and drink almost anything,” he explains further in the book, is prerequisite to conducting business abroad—especially in Asia. “The [20-plus course] banquets are still often a challenge.”

Perkins describes the moment in 1994 when the firm’s leadership made the conscious decision to pursue more international work after several early projects in Spain, Italy, and South America. “We were 50 people and one office in New York. A number of us were interested in international work, but we were not a brand name. We didn’t have a whole lot of built work, so we looked at where we could get projects,” he explains. “We realized that Asia was the most likely place where we could realistically have a chance, just because there was so much work.” China in particular, he writes, is the largest construction market in the world. “China’s determination to match and pass the more developed parts of the world has created immense opportunities for North American design firms,” where projects in China today can also lead to commissions from the same client in the United States. Even better, he continues, “in spite of the occasional periods of tension with the West, the Chinese people like Americans and Canadians.”

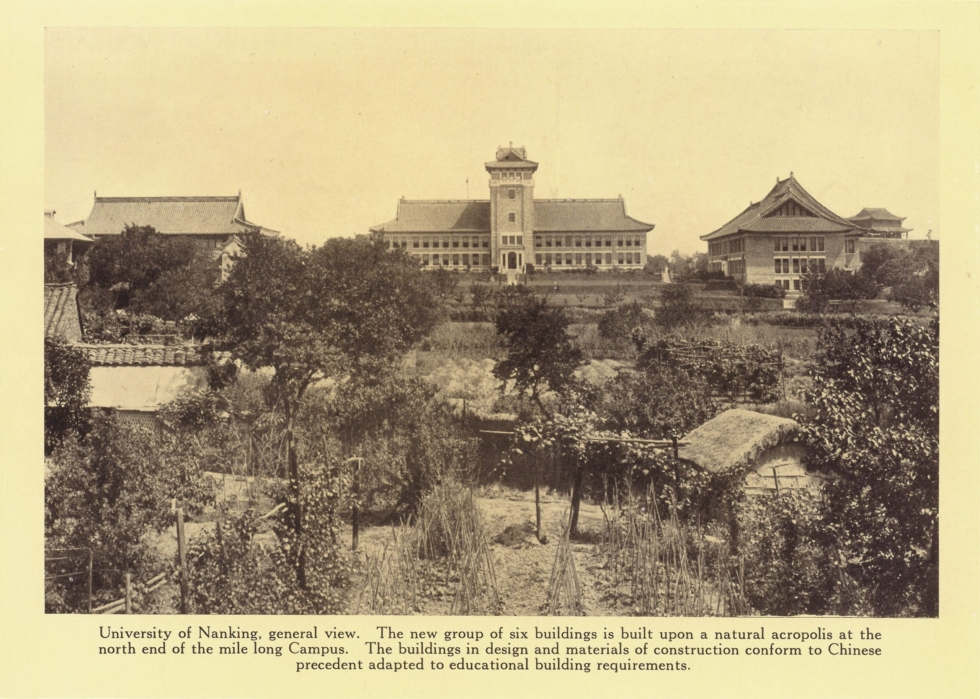

Of course, it also helps when your grandfather, Dwight Heald Perkins I, designed two universities there in the early 20th century; your father Lawrence Perkins’ firm, Perkins & Will, holds a large presence there—and your brother, Dwight Heald Perkins II, is Harvard’s top China scholar whose former students include current government leaders in the region. “I knew this was a place I wanted to go back to and could see myself committing to,” Perkins says. The lesson here? “Consider your own networks, family, and close friends” when choosing where to pursue work. “A lot of international commissions come through personal relationships.”

Perkins Eastman designed a comprehensive master plan for the city of Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital.

One of Perkins’ earliest commissions in China—the prize after winning one of the aforementioned drinking contests—was the design of a new city for 100,000 people. The massive scope of those early forays helped Perkins Eastman establish a higher profile both abroad and at home. “It was something to make us look more interesting and sophisticated,” he says. International projects also offer freedoms that might not be possible in the United States, he writes. “The scope and challenge of some overseas projects is unmatched domestically. For those who find the opportunity to design multimillion square-foot mixed-used developments, entire new university campuses, and new cities exciting, most of these opportunities are overseas.” Perkins lights up when he describes designing a new comprehensive master plan for Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam, and a new campus for Ashoka University outside of Delhi in India: “Since I’m both an architect and a planner, some of the highlights of my career in both disciplines have been overseas.”

Ashoka University’s architecture combines traditional aesthetics with modern forms.

Photo, copyright Harshan Thomson

Cautionary Tales

Perhaps it can go without saying that working abroad is not for the faint of heart, but Perkins—characteristically—can tell you why. “Part of the reason for the book is so people can avoid mistakes,” he says. “I’m not averse to risk, but I don’t usually put all my chips on the table.” Chapter 9 is full of case studies about prominent firms that have perished through international expansion or got taken in by convincing con artists. Stories about staff suffering serious health issues without access to good doctors, and being caught in countries where violent uprisings erupt and kidnappings are common are part of the mix. “Swapping stories about our disasters is a favorite, masochistic pastime for some international architects,” writes Perkins, who doesn’t spare Perkins Eastman in his accounts. “We hope we have learned the appropriate lessons.”

The book is a primer on how to avoid losing money through poorly negotiated contracts, or spending too many resources on ubiquitous design “competitions” where the winners are frequently predetermined. It offers guidelines for licensing and insurance—areas where companies can get into serious trouble if either is lacking. Above all, Perkins cautions, don’t get lured by invitations for bribery, a federal felony that could put you and your entire firm out of business. The book’s appendix provides the complete text of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act’s antibribery provisions. Most international clients are unaware of the law.

What’s Next?

Moving into a post-pandemic future, Perkins sees continued growth for the firm in Asia, South Asia, the Middle East and South America that will keep the studios in Shanghai, Mumbai, Dubai, and Guayaquil busy.

Advances in technology have certainly helped the firm continue its work abroad through the shutdown, even though Perkins and other U.S. project managers can’t be on project sites in person in most cases. “On one hand, it’s worked better than expected, but it isn’t the same,” he says. “All my clients around the world are going to expect to see me when it’s once again safe to travel.” And Perkins is eager to put those next stamps in his passport.