Think about some architectural or landscaping elements that can add to a building’s character. Are they columns at the top of wide, limestone steps? Maybe some shade trees that drape over the sidewalk? Or an open, industrial stairway that rises up through a lobby? They’re all lovely gestures for sure, but San Francisco architect Chris Downey would like us to “see” those things without our eyes.

Architect Chris Downey navigates a sidewalk in San Francisco. Photograph © Rosa Downey

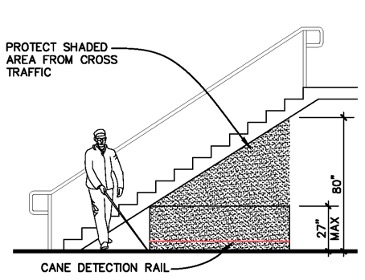

Downey is blind. That means columns without setbacks, for instance, pose a (painful) greeting at the top of those steps. Low-hanging tree branches impede his path, even when his cane suggests an open sidewalk. Same thing with the cool floating stairway if he’s approaching from the side—the cane goes underneath it while he walks right into its I-beam stringer.

Downey spoke to the Perkins Eastman staff on Wednesday, just ahead of International Day of Persons with Disabilities, which is recognized globally each year on December 3. Downey revealed to the firm his world as a blind architect—and his mission to help sighted professionals think about design in new ways to provide beauty without barriers. “We’re architects,” he said. “We’re trained not to shrug away from challenges. We revel in the unknown. We revel in the exploration.”

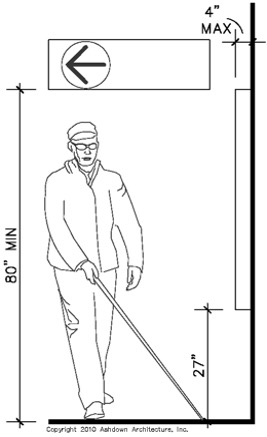

Downey was used to following code requirements before he went blind, he told Perkins Eastman, but once he became the man in the diagram, they developed a whole new meaning:

Left: Photograph © Richard Skaff. Right: Courtesy Architecture for the Blind

Downey has been exploring these unknowns since 2008, when he became blind following an operation to remove a brain tumor that was near his optical nerve. At the time, he was 45 and led a “rather robust, typical practice” as its owner and principal. Within hours of learning his condition would be permanent, he found himself listening to a social worker tell him about “career alternatives.” After all, how could an architect be blind? That was the moment he resolved to live out the answer. His journey, which he’s described in TED talks and has been profiled on 60 Minutes, has led him to believe there’s a beautiful power in disability. “We have to get away from the deficit model of disability,” he told the Perkins Eastman staff. “It can be additive. You can find new values, new possibilities,” rather then feel lost in the notion that “I can’t.”

The Tennessee native grew up in a world of Southern hospitality, for example, where everyone in his community would stop and say hello, but he had to tamp down that instinct when he moved to the city. Once he became blind, however, “now people were speaking to me” as he navigated the sidewalks and crosswalks with his cane, giving him greetings of encouragement, or stepping in to offer help if he was headed toward an obstacle. “There’s lots more engagement when you’re blind,” he said. “That’s the power of disability, to bring everyone together.”

Downey calls these post-sighted discoveries “Outsights.” Rather than listen to the social worker, he was back in his office a month later, even before starting the intensive training on things like reading Braille, learning text-to-speech computer software, using a cane, and navigating public transportation. “They don’t like it when we drive,” he likes to joke.

He also found new tools for his job. He gets floor plans and elevations printed with embossed lines so he can “see” them by touch, and then uses children’s wax craft sticks to mold suggested changes on top “like a trace overlay on base drawings.”