Climate change and resiliency weren’t big talking points in the early Aughts, when Perkins Eastman Principal Eric Fang (then with EE&K, which ultimately merged with the firm) took the lead on a master plan for Arverne by the Sea, a mixed-use development on the sensitive Rockaway barrier peninsula in Queens, New York. “We had raised the question about sea level [rise], which at the time was not something that people were talking about a lot,” Fang says. Nonetheless, the plan provided for raising the community five feet higher above sea level, landscaping a double-dune buffer from the ocean, and installing a large network of underground stormwater catchment areas. Utility lines were also laid underground along with flood-resistant submersible transformers.

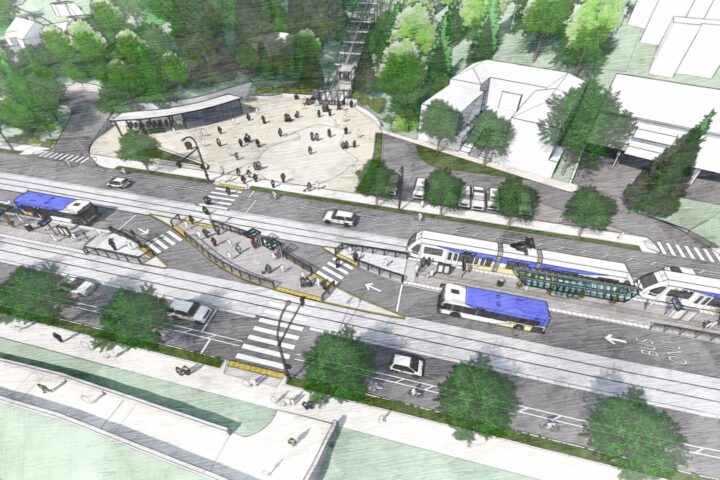

Fast forward to the onslaught of Superstorm Sandy in 2012, when Arverne survived largely intact—an island amidst devastation all around it. The project set an example for many more to come, establishing Fang and Perkins Eastman as experts in planning for resilient communities. Every year since that storm, Fang says, the firm has taken on at least one major resiliency planning project as a result. Fang also serves on the statewide New York Rising Community Reconstruction Program, designed to consult with communities, residents and business owners on storm resilience and recovery. And following our merger with VIA Architecture in July, 2021, the firm has added significant west-coast expertise in resilient transit-oriented development.

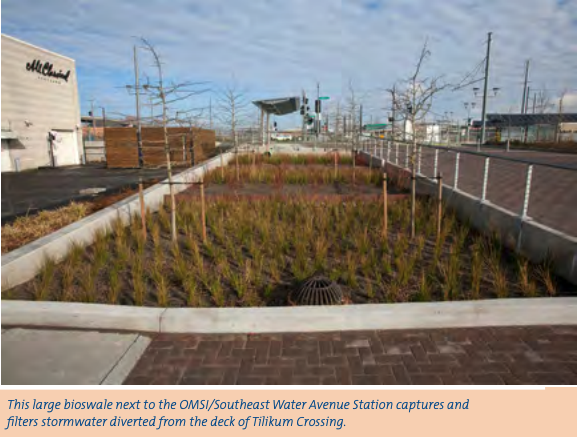

The definition of resiliency in the built environment differs according to the needs and location of each project, Fang explains, but it’s always grounded in the same philosophy, which is that a diversity of solutions—both natural and man-made—plus a redundancy of systems need to work together to protect towns, businesses and homeowners from climate-driven destruction. This worldview departs from the traditional one-size-fits-all tendency toward “gray infrastructure—sea walls, culverts, pipes, hard stuff—and that’s really been the approach for the last hundred years,” Fang says. Green infrastructure, on the other hand, works with nature and not against it. Open swales, trees, rain gardens, constructed wetlands, and green roofs are among the more natural alternatives that can do a better job. By providing a diversity of infrastructure strategies, communities can adapt to a variety of future scenarios. “You need to have a larger vision and compelling strategy to pull together the complex actions needed to build community resilience,” Fang explains. “It can’t be just a laundry list of best practices. It’s going to be a different future, and we’re going to have to live with the water.”