Everyone is neurodiverse

The terms “neurodivergent” and “neurodiverse” are sometimes used interchangeably, but they have distinct meanings. Neurodivergent describes individuals whose brains function differently from what is considered “typical.” It includes people with clinical conditions like Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD), but it also encompasses a wide range of other cognitive differences.

Neurodiversity, on the other hand, refers to the entire spectrum of differences across all human brains. Armita Hosseini, a psychological associate specializing in neurodivergent conditions and clinic director of Talk and Thrive, points out that no two brains are exactly alike. Even for those with “typical” attributes, there are differences in how they sense, perceive, and interpret their experiences.

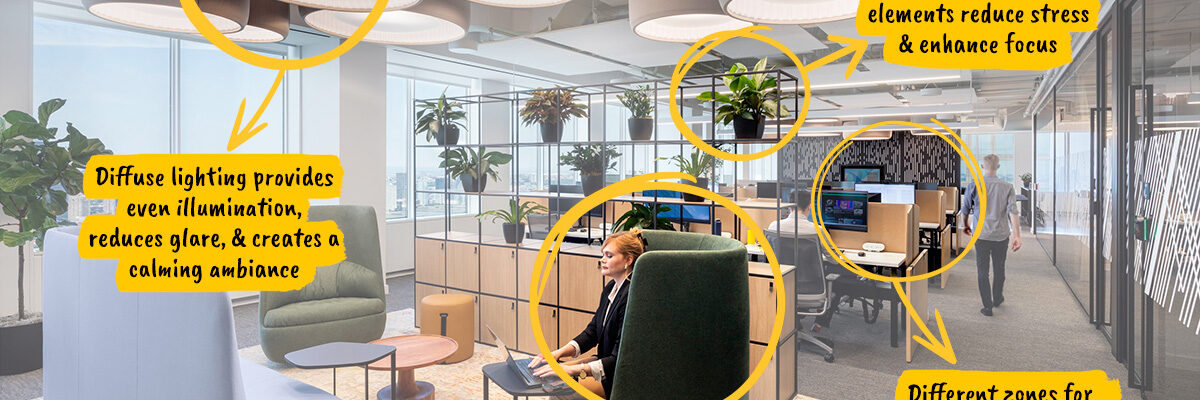

According to Hosseini, designing for “average” leaves important workforce assets on the table. Neurodivergent individuals often have high levels of creativity, and their talents can provide a lot of value in the workplace. But when they’re thrown into an environment that isn’t a good fit, their unique contributions can go untapped.

The business case for inclusive design

Talent is expensive. In fact, companies spend as much as 70 percent of their total operating costs on labor. Why invest so much in your workforce and only tap into a fraction of its potential?

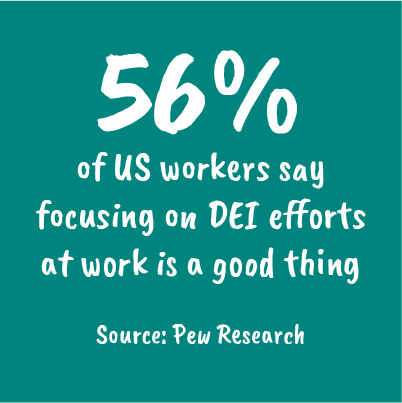

Inclusive design and practices unlock that potential by helping everyone perform at their best. Research strongly supports the business case for these investments, linking workplace diversity to higher employee engagement, innovation, and productivity, among other positive outcomes:

Ms. Armita Hosseini is a registered psychological associate and member of the college of Psychologists of Ontario (CPO) and the clinic director of her own clinical practice, Talk and Thrive Psychology. She is a member of the International Society for Autism Research (INSAR), Canadian Psychological Association (CPA), and Ontario Psychological Association (OPA). Ms. Hosseini specializes in clinical and counseling psychology with expertise in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and other neurodevelopmental disorders.

Ms. Armita Hosseini is a registered psychological associate and member of the college of Psychologists of Ontario (CPO) and the clinic director of her own clinical practice, Talk and Thrive Psychology. She is a member of the International Society for Autism Research (INSAR), Canadian Psychological Association (CPA), and Ontario Psychological Association (OPA). Ms. Hosseini specializes in clinical and counseling psychology with expertise in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and other neurodevelopmental disorders.