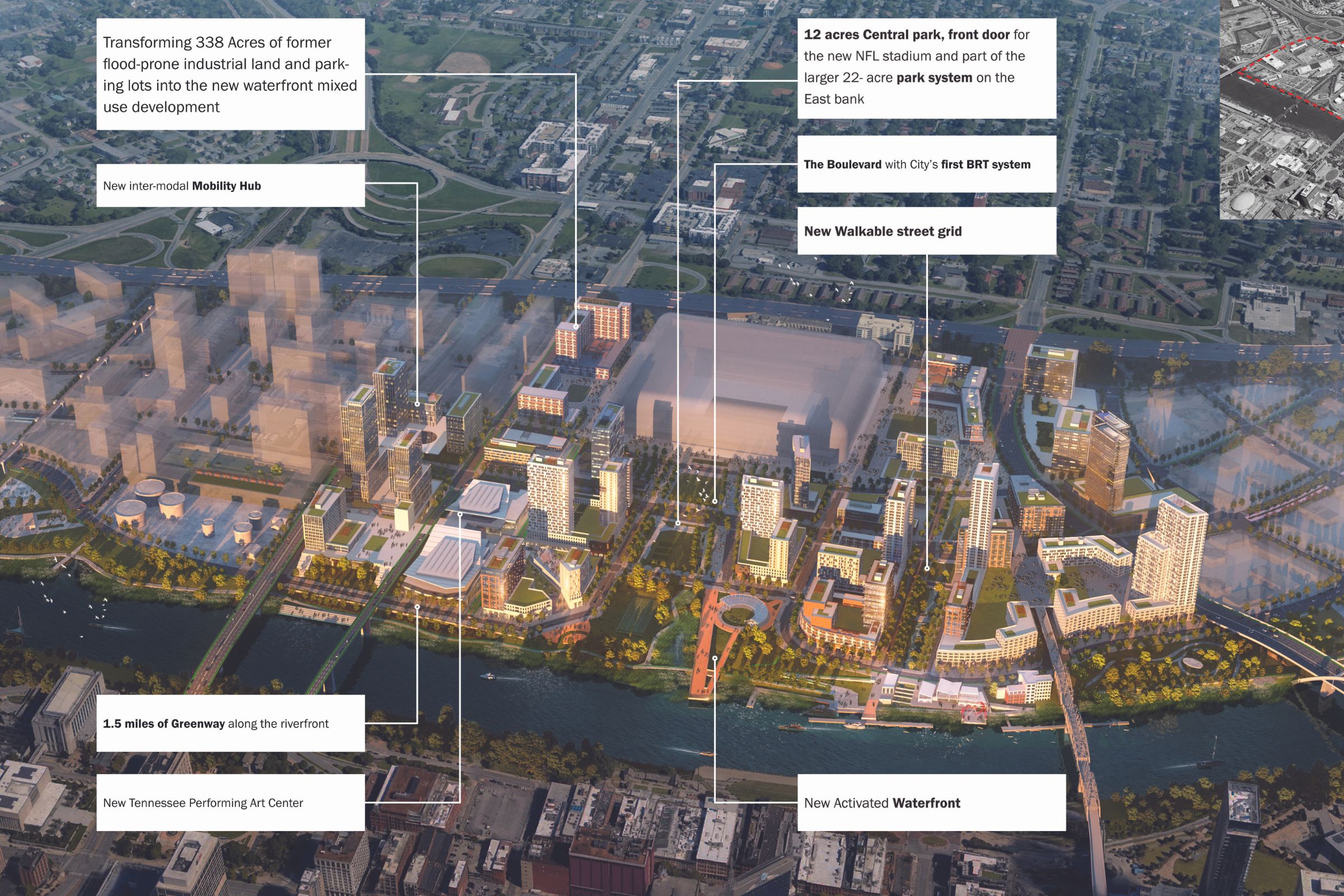

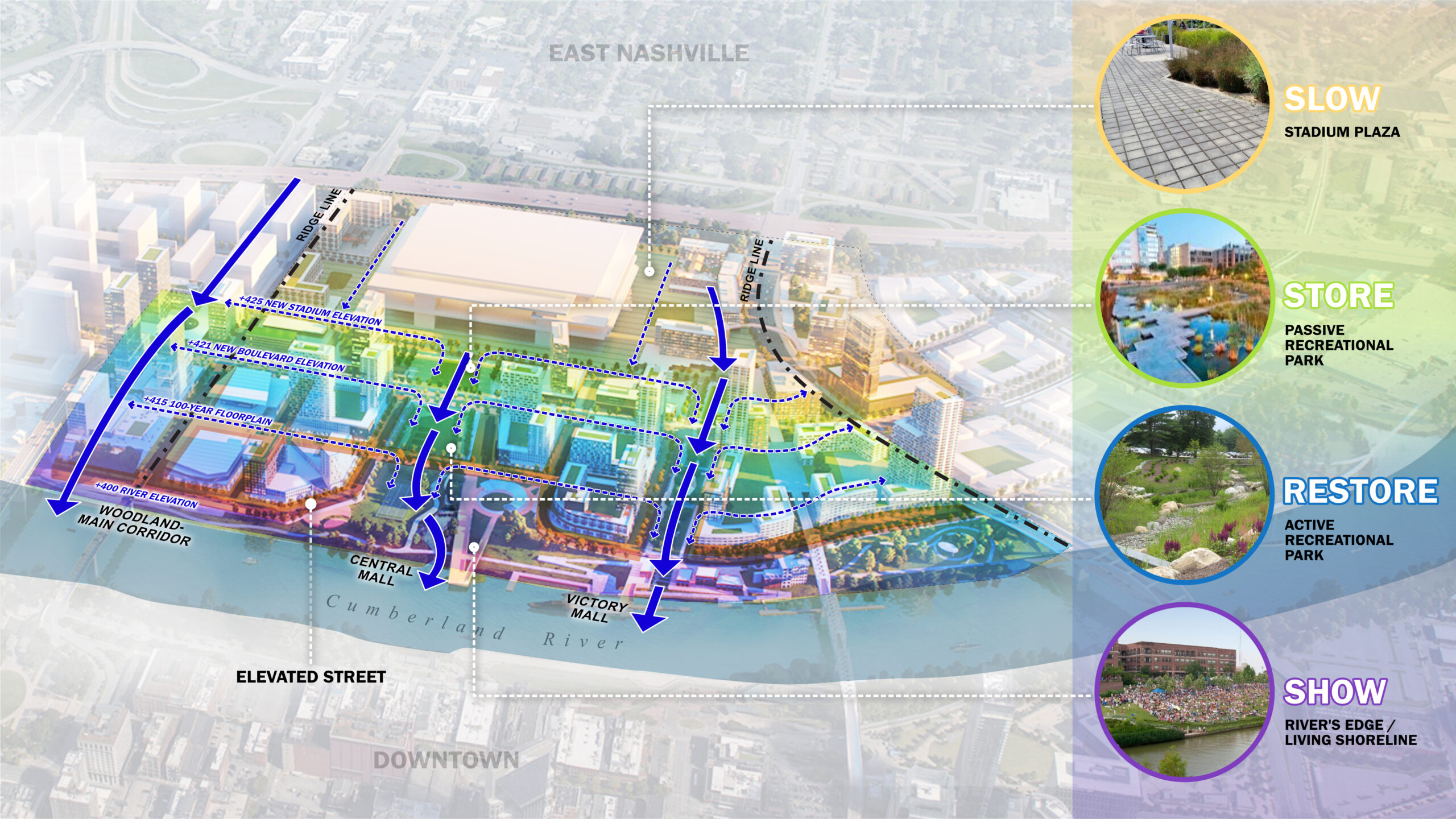

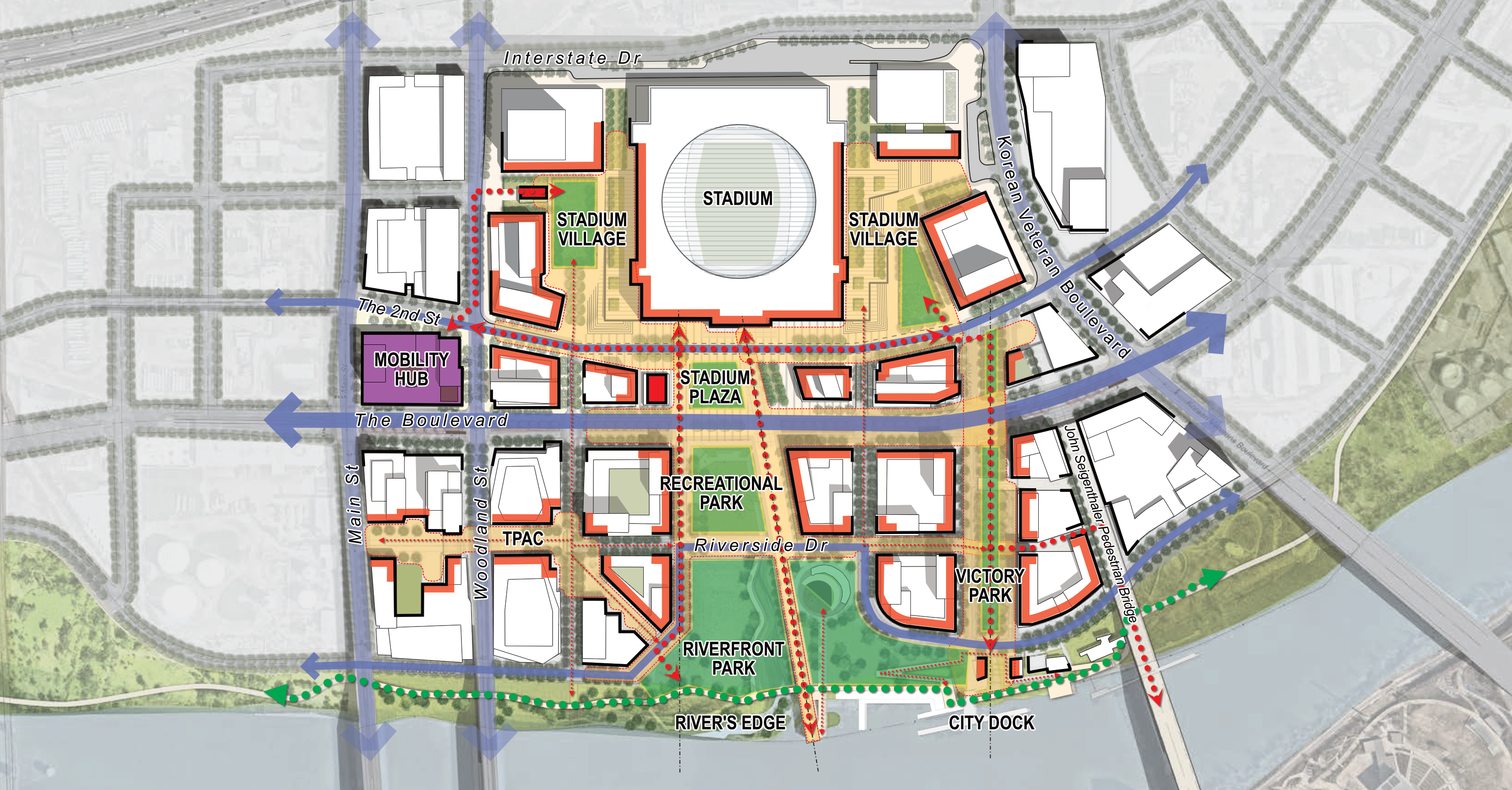

Transportation plays heavily into the plan as well—a large-scale vision that’s only possible because the city manages such a huge swath of the East Bank property, giving its planners a “blank slate” to work with. And that’s good, considering the current situation. “Driving from one end of Nashville’s East Bank to the other currently means navigating a disjointed network of streets around parking lots and industrial properties,” requiring at least five turns in the process, the Nashville Tennessean noted. The entire East Bank strip, which includes a large parcel Oracle intends to develop as its new headquarters and the River North district, where private landowners are developing hotels and residential buildings, “is today cut in half by the concrete wall of the James Robertson Parkway Bridge. Interstate 24 divides the East Bank from the more walkable streets of East Nashville,” the newspaper wrote.

Perkins Eastman’s plan proposes bringing that bridge down to grade, rerouting a network of CSX freight tracks, and establishing a wide, straight boulevard—currently in design—as East Bank’s north-south spine, where pedestrians, cyclists, and buses, and cars will have equal access.

The Boulevard will act as the East Bank’s central artery for transit, auto, pedestrian, and bike traffic. “The Boulevard has to be, first and foremost, a public place for people,” Metro Planning Director Lucy Kempf told the Tennessean.