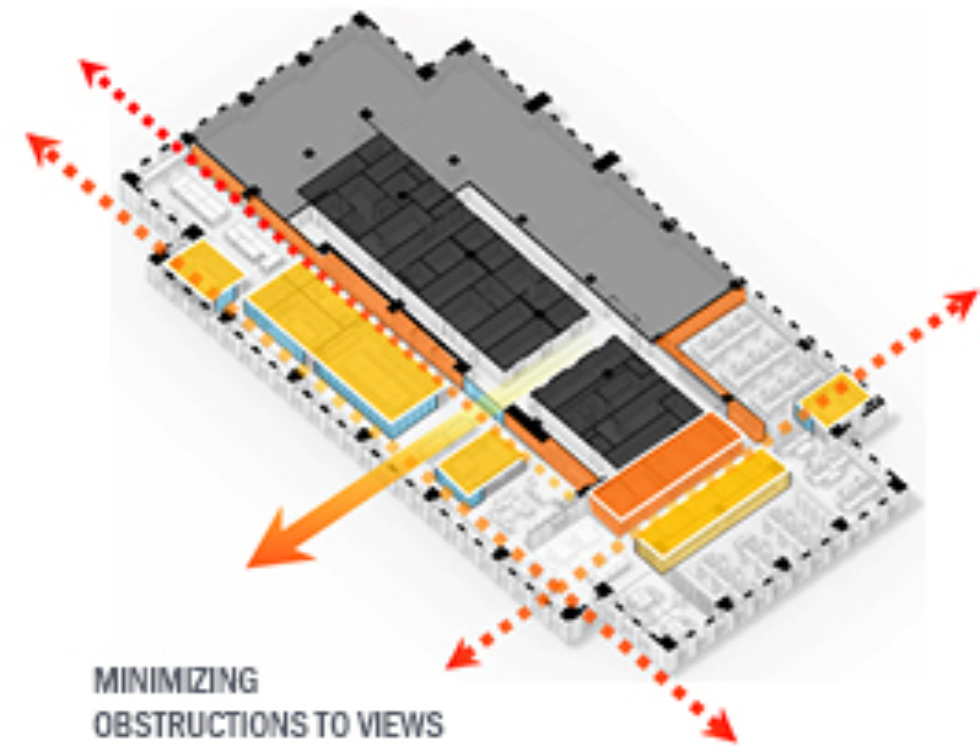

A major finding of the POE was how the free-address, non-hierarchical seating allows more intermingling between junior and senior employees of all roles. The arrangement provides more opportunities for spontaneous collaboration and informal mentorship (e.g., day-to-day coaching and knowledge sharing). The researchers coined the term “eaves-learning,” which they define as “the process of acquiring knowledge and skills from eavesdropping, informal mentorship, and spontaneous collaboration that occur when working in close physical proximity to other people.” Key to this is physical proximity, as eaves-learning is nearly impossible to replicate in highly scheduled digital meeting environments.

Of the many positive statements, one Pittsburgh employee summed it up best: “I want to go into the office now because it feels like a healthy, clean, bright place to be. I also value the non-hierarchical office environment, which fosters our mentorship culture. Our office does a good job supporting us and working with us. Now, the office is more like a tool we can use.”

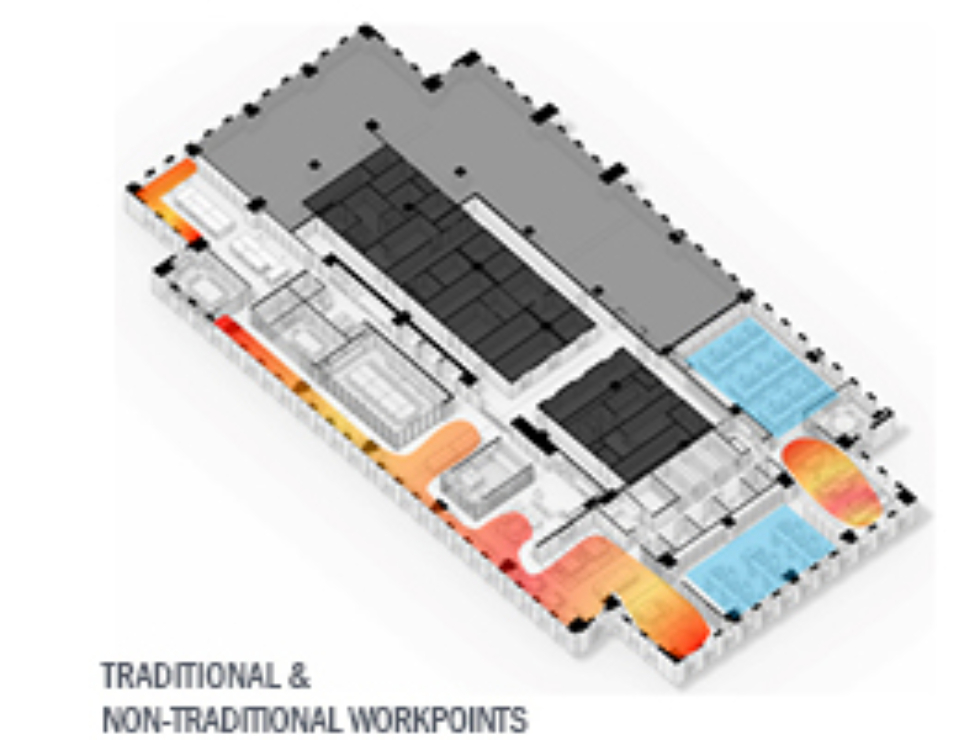

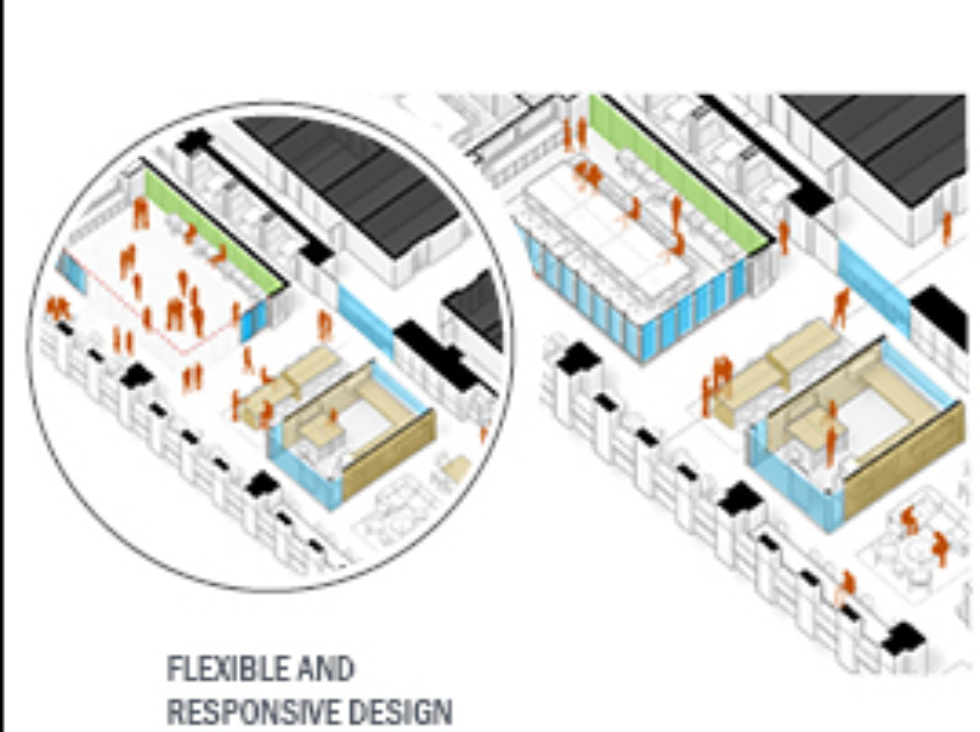

The workplace is designed to be flexible and adaptable, with an assortment of multi-purpose features.

Photograph Andrew Rugge/Copyright Perkins Eastman

Constructive Criticism

Of course, there are also some drawbacks. Many communicated a need for a better integration of work postures, (for instance, spaces to collaborate with team members within the areas reserved for traditional sit/stand desks). Though there are thermostats and temperature sensors throughout the office, some reported that the space generally ran a bit cold. And the studio’s clean-desk policy, which calls for cleared-off workspaces at the end of each day, conflicted with the creative and messy energy of a design firm. For the short-term, these issues are being addressed through amendments to policy: several locations in the office have been identified where teams can settle in for multiple days, leaving drawings, models, and other project materials out to ease the burden of reassembling every morning, allowing creativity to flow more freely. Changes to layout can also be addressed as time and budget allow, which speaks to the adaptability of the original design. For example, where the workstation neighborhoods are now reserved for rows of sit/stand desks, some may be swapped for high-top tables and stools in the future for easier face-to-face collaboration within these spaces.

Jennifer Askey, an associate principal and the project manager for the Pittsburgh studio project, was pleased with the evaluation’s findings that showed how well the goals and outcomes of the project seemed to align. “When we were planning,” she says, “we were really focused on how to blend policy and design to reinvigorate our culture. The pandemic shifted so many of the ways people interacted with one another, and we needed to learn from that and adapt.” The resulting free-address design and work-from-anywhere attendance policy was an attempt to bring staff physically back together again while maintaining some of the comfort and flexibility that they had while working from home. “I feel like we got all of the fundamentals correct and we were flexible enough with the design that all of the POE’s recommendations could either be implemented through changes in policy or by future furniture improvements,” she says.

The Workplace team has already begun sharing these findings with clients and adapting ongoing designs based on their new knowledge. Law firms in particular—including Dickie McCamey Attorneys at Law, (whose managing attorney first toured the Pittsburgh studio with Young)—are eager to incorporate more collaborative, casual spaces into their floorplans. Their future workplace, for example, includes the necessary private offices for their attorneys but features gathering and shared spaces with a variety of seating and amenities for a more casual yet on-brand approach.